The Rio 2016 Olympic Games show everyone outside the country something that previously only Brazilians could understand: non-stop energy for celebrations and happiness in the face of struggle. This mixture makes our Brazil a unique nation. We face political instability and problems with infrastructure, and worst of all, we lost the chance to win our sixth World Cup in football. But Brazilian virtues and strengths prevail, and we believe that this Olympic mega global sports event will help us overcome the struggles of our past.

I am a journalism student in São Paulo, serving as a field producer and Portuguese translator for a group of Queens students. A ticket purchase at the last minute gave me access to a stadium on Copacabana beach, a sand stage for beach volleyball, a sport that perfectly reflects the culture of Rio de Janeiro. Watching this event required us to depart from our hostel at about 8 a.m., but the sun was still hidden behind clouds, looking like it was still asleep. A cold breeze and drizzle translated into a less than ideal day at the beach. None of this ruined the Olympic atmosphere. Emerging from the subway stop, a few blocks from the beach, we saw the flags of dozens of nations translated into colorful and creative props. They were scarves and shawls, t-shirts and flags, towels and hats. It’s an inspiring sight to see city blocks transformed into a United Nations assembly of ordinary people like you and me.

“It’s going to be like a soccer game,” I thought: loyal fans cheering for their teams, distracting themselves between moves by eating their popcorn. My mistake. It’s a noisy and boisterous crowd at an Olympic beach volleyball game, and Brazilians on their beach at Copacabana make it even crazier. Newcomers start out timid, but emcees and dancers provide energetic instructions on gigantic video monitors in how to join the party. If a “monster block” happens, you raise both hands. See an “ace ace”? Form a Y over your head and clap your hands. See a “super spike”? I don’t really remember, but there seemed to be a lot of waving and yelling “boom chicka boom.” Beer was flowing freely, and I don’t think the rest of the crowd remembers much, either.

The first match was a little boring. Not much Brazilian excitement. Then the United States men played against Spain. Fans near me, who had watched the first game quietly, now made constant observations like they were volleyball experts. The American guys, Casey Patterson and Jake Gibbs, got really angry about a call by a referee. The crowd, mostly Brazilian, booed. They booed a lot. I am also an exchange student at a university in Kansas, and I felt sympathy for my American friends in the stadium. But the Americans lost, and I heard later that one of the American guys stormed off the court. The crowd did the wave.

From that stunning view at Copacabana – a stadium perspective I never imagined being able to experience — I realized that more than medals, more than athletic competition, the real legacy of these Olympic Games is knowledge of the Brazilian way of life. Brazilians often say that São Paulo is the New York of Brazil, and Rio the Los Angeles. In a disorganized, unpredictable, and beautiful city like Rio, you must be tolerant. The cariocas of Rio wake up every day with a smile, ready to help whoever needs it. They are fighters. Even if victory does not come today, even if our women’s football team loses to Sweden, even if we lose another World Cup, we keep going after our goals. Seeds of hope are planted deep within us. In times of chaos and violence, there is still a chance for rivals – athletes, in this case – to coexist in harmony. In those temporary bleachers at Copacabana, in those flag-filled city blocks, maybe we aren’t just supporters of isolated countries waiting to cheer for a first-place team. For a few Olympic days, perhaps all of us are Brazilians.

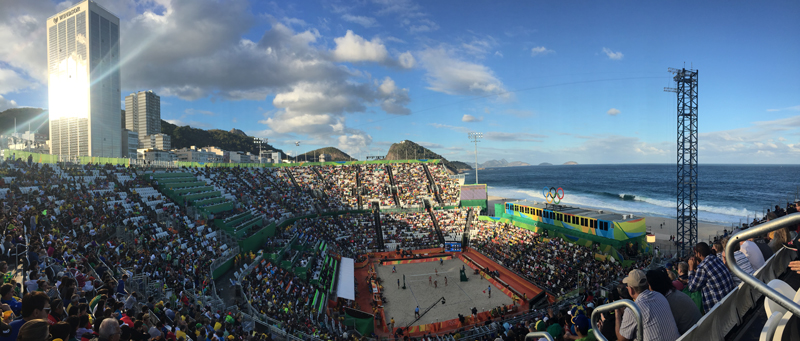

Above: photo of Rio 2016 Olympic Games beach volleyball venue by Joe Cornelius